30 Apr Biosecurity Best Practice – May 2021

Spotted something unusual in your grove?

Sharp eyed OliveCare® member Jackie Courmadias of Golden Creek Olives, Victoria spotted this in her olive grove:

The insect on the left is obviously Black Olive Scale Saissetia oleae, a common and potentially destructive pest of olives – but what is that amazing structure on the right?

According to olive industry entomologist Associate Professor Robert Spooner-Hart, this is likely a pupal cocoon of Brown Lacewing, Micromus sp. a beneficial insect species, whose voracious larvae eat soft bodied pests such as aphids and mealy bugs, as well as eggs of other pests – so don’t kill this one!

Black Olive Scale Saissetia oleae

Black Olive Scale References:

Ref: [1]IPDM Resources (OL17001): Olive Black Scale Flier by Robert Spooner-Hart et al (2020).

Ref: [2]IPDM Resources (OL17001): Field Guide (Second Edition) by Robert Spooner-Hart et al (2020) – Sooty Mould pg 61.

Ref: [3]Managing Black Scale in Olives (AOA 2016).

Ref: [4]Management of Black Scale and Apple Weevil in Olives (RIRDC 12/019) by Sonya Broughton and Stewart Learmonth.

Ref: [5]Management of Black Scale and Apple Weevil in Olives (Review December 2019) by Sonya Broughton and Stewart Learmonth.

Control options for Black Olive Scale

The following formulations are approved by the Regulator for use on olives for the control of Black Olive Scale Saissetia oleae

The heavy hitters:

Group 4A: Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) competitive modulators (Neonicotinoids)

- PER 89943 Trivor Insecticide (acetamiprid + pyriproxyfen) Permit to 31 January 2024, Group 4A (Neonicotinoid) and Group 7C (Insect Growth Regulator)

Permit: https://permits.apvma.gov.au/PER89943.PDF

Use: Maximum of 2 applications per season. Withholding Period 28 days

- Victoria Only: Bayer Confidor 200 SC Insectcide, Group 4A Insecticide (neonicotinoid),

Note: Under Victorian control of agri-chemical use legislation, Victorian olive growers have broader use options.

Group 7B: Juvenile hormone mimics (Fenoxycarb)

- Registered Fenoxycarb (Insegar): Group 7B insect growth regulator,

Label: https://www.syngenta.com.au/product/crop-protection/insegar-wg

Use: Maximum of 2 applications per season. Withholding Period 56 days

Group 7C: Juvenile hormone mimics (Pyriproxyfen)

- PER 89943 Trivor Insecticide (acetamiprid + pyriproxyfen) Permit to 31 January 2024, Group 4A (Neonicotinoid) and Group 7C (Insect Growth Regulator)

Permit: https://permits.apvma.gov.au/PER89943.PDF

Use: Maximum of 2 applications per season. Withholding Period 28 days

- Registered Pyriproxfen (Admiral), Group 7C Insecticide,

Label: https://sumitomo-chem.com.au/sites/default/files/sds-label/admiral_adv_label_0.pdf

Use: Maximum of 2 applications per season. Withholding Period: 7 days

Organic and other “soft” control options for Black Olive Scale:

- Biological control options: Black scale has been the subject of biological control projects in the Australian citrus industry since 1902. From 1902 to 1947, 24 species of beneficial insects (22 parasites, two predators) were released for its control.

- These included Metaphycus anneckei in 1902 from South Africa and M. helvolus 1943–47 from the USA. From 1998 to 2003, M. helvolus and M. lounsburyi were released in citrus as part of a Horticulture Australia Ltd-funded project.

- Surveys as part of a Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation project in WA showed that the egg predator, Scutellista caerulea, is most common. M. helvolus and M. anneckei are poorly established.

- The effectiveness of caerulea is limited, because populations build up too late to prevent scale outbreaks.

- Establishment of helvolus and M. lounsburyi in olives is recommended. However, there may be problems in obtaining insects commercially for release.

- General predators such as lacewings and ladybirds also feed on black scale.

- Ant control is required where growers are interested in pursuing biological control, as ants harvest honey dew from black scale, and protect the scale from parasites and predators.

- Potassium carbonate and potassium bi-carbonate are foliar nutrients that may have incidental contact agent pest control properties

- Horticultural spray oils are simple, easy to use safely, and are kinder to beneficial insects, but they do depend on the spray fully “wetting” the instars and insects. Since the instars and insects live on the underside of olive leaves, the spray equipment must be set up carefully to saturate the undersides of the leaves right across the tree. Label:http://websvr.infopest.com.au/LabelRouter?LabelType=L&Mode=1&ProductCode=59092

Note: Paraffinic and vegetable oils (including olive oil) – contact agents – potential low toxicity organic options – however there are implications for use of vegetable oils (other than olive oil) on EVOO fatty acid profile.

[1] IPDM Resources (OL17001): Black Scale Flier: https://olivebiz.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/BLACK-SCALE.pdf

[2] IPDM Resources (OL17001): Field Guide (Second Edition): https://olivebiz.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Field-Guide-2nd-edn-revised_2.pdf

[3] Managing Black Scale in Olives (AOA 2016): https://australianolives.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/FACT-SHEET-Black-Scale-2016.pdf

[4] Management of Black Scale and Apple Weevil in Olives (RIRDC 12/019) by Sonya Broughton and Stewart Learmonth: https://www.agrifutures.com.au/wp-content/uploads/publications/12-019.pdf

[5] Management of Black Scale and Apple Weevil in Olives (Review December 2019) by Sonya Broughton and Stewart Learmonth: https://australianolives.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Management-of-Black-Scale-and-Apple-Weevil-in-Olives-a-review-Dec2019.pdf

Queensland Fruit Fly (Q-fly) stings Hunter Valley table olive groves:

Associate Professor Robert Spooner-Hart has flagged fruit fly to be “occasionally important” in the Hunter in his chapter in the HOA handbook.

The Queensland fruit fly (Q-fly) Bactrocera tryoni, is occasionally reported damaging olive fruit. Q-fly is endemic to Queensland and the coastal parts of New South Wales, including the Hunter Valley. Fruit is damaged by oviposition, which can prematurely ripen fruits or cause them to fall. This damage also predisposes fruit to fungal rots. There are commercially available baits (Cue-lure, methyl eugenol) used to trap males, mainly for monitoring, and baits for female flies but these are likely to have limited effect, especially in seasons of high fly populations. There are currently no chemicals registered for use against Q-fly in olives.

According to olive industry entomologist Associate Professor Robert Spooner-Hart “this season is likely to be a shocker for fruit flies in many crops. The high rainfall/ humidity experienced in the Hunter Valley in 2021 has resulted in high Q-fly populations, with olives being one of the fruits still around at this stage in the season. In particular it is the large-fruited table olive varieties that seem to be most attractive/susceptible.”

Unfortunately, there are no chemical control options directly available. The permit for dimethoate on olives has been extended to the end of March 2022, but does not include fruit fly on olives, (withholding period 28 days). Industry has a new product, Trivor® that is permitted in a number of crops for fruit fly suppression, but at this stage for olives, it is only for olive lace bug and scales (withholding period 28 days). Samurai® (currently permitted for olive lace bug) is legal for fruit fly in a number of other fruit crops, but its long withholding period of 56 days would exclude use for olives at this stage in the season.

Legal options (probably no point now, as it’s a bit late for this season) include using baiting with protein hydrolysate/yeast autolysate mixed with the human-safe safe insecticide spinosad, https://bugsforbugs.com.au/product/naturalure-trade-fruit-fly-bait/ (also see spinosad label attached), or mix protein hydrolysate/yeast autolysate with maldison (these are is trunk treated, and must not contaminate fruit) . Also, you should monitor earlier in the season (say mid-late summer) for presence of fruit flies with fruit fly traps- however, these only attract male flies, so aren’t effective for control.

ED: AOA has recently contacted Hort Innovation with a request to pursue a label variation with the registrant Adama, to enable the use of Trivor® for fruit fly suppression – watch this space.

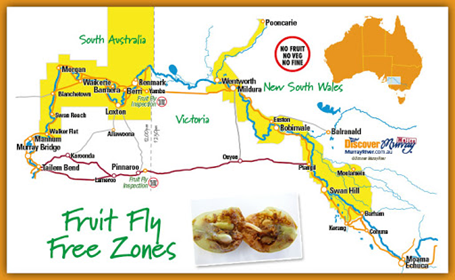

The Fruit Fly Exclusion Zones of NSW, VIC and SA.

Major horticulture production regions located along the Darling and Murray Rivers in NSW, Victoria and in SA enjoy status as fruit fly free zones. This provides significant economic benefit to producers through the movement of fruit to interstate and overseas markets without the need for expensive fumigation / disinfestation.

Hence quarantine authorities, and industry in these states dedicate significant resources to controlling fruit movement and people into these production areas in order to maintain area freedom status.

Unfortunately from time to time outbreaks do occur and fruit movement restrictions, and eradication processes are then put in place to eradicate the pest:

Red Zone: within 1.5 km of the fruit fly detection (both Q-fly and Med-fly) – no movement of fruit fly host material out of the red zone is permitted

Yellow Zone: from 1.5km out to 7.5 km of a Med-fly fruit fly detection, or from 1.5km out to 15 km of a Q-fly fruit fly detection – fruit movement into the green zone permitted subject to official fruit movement treatment protocols

Green Zone: no restrictions on fruit movement.

How long are fruit movement restrictions in place?

The time it takes to complete one fruit fly generation (which varies depending fruit fly species, on the weather and time of the year) plus 28 days or 12 weeks from the last detection, whichever is longest. As a general rule this is between 12 weeks and 9 months.

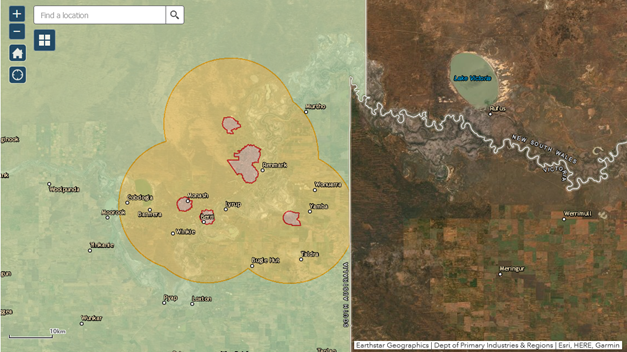

Outbreak of Q-fly in the Riverland of SA impacts olive growers:

Riverland olive growers are caught up in the current Q-fly outbreak, and are unable to send their harvested olives out of the yellow suspension zone into the green zone for processing.

Whilst olives are not considered a major host of Q-fly (or Med-fly), it is a potential host (under high pest pressure) so quarantine authorities are treating olives as a Q-Fly host crop which means there are restrictions in place of movement of olives out of the Red and Yellow Zones (effective to 24 November 2021):

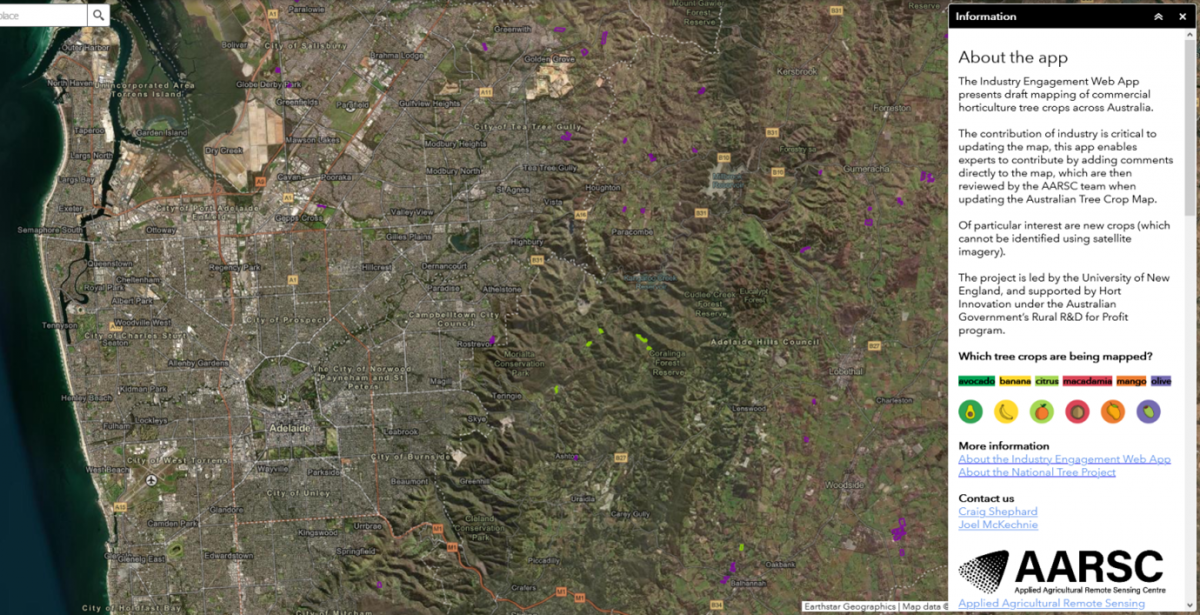

With reference to the PIRSA fruit fly outbreak map below and the Australian tree crop mapping project, map below there appears to be around 15 olive blocks in the Riverland outbreak area – 14 in the Yellow Zone and 1 in the Renmark Red zone (shown as purple spots):

According to PIRSA quarantine advice key fruit fly treatments available for produce from within a Suspension Area are:

- Pre-harvest treatment and inspection ICA arrangements (various eg table grapes – contact us for more information). Only accepted by NT, VIC, NSW and SA markets outside of the Riverland.

This is a bit late for the current season as treatment protocols would need to be negotiated and bait sprays used for the required period pre-harvest.

- Dipping/spraying of some hosts with Dimethoate under Biosecurity SA – Plant Health supervision or by self-application using ICA-01 / ICA-02 accreditation

This is not appropriate for olives

- Cold Storage (ICA-07) – requires 16 days of cold treatment at 2 or 3 degrees.

*There is some evidence that olives will hold up in refrigeration for a couple of weeks without compromising quality, but this is an unwelcome additional cost.

- Fumigation with Methyl Bromide (ICA-04)– to be undertaken in an approved specialist facility – 2 hours of fumigation at a specified bromide concentration at >17 degrees (plus 3 day withholding period before processing)

Also a possibility for olives but this is an unwelcome additional cost.

- Movement of Winegrapes (ICA33)# – noting that there are other options available for treatment and secure transportation. ICA33 allows harvested grapes to be transported in a covered load to a secure winery for processing within 24 hours.

#ED: This option for olives is currently being negotiated by AOA with PIRSA.

*Cold storage of olive fruit:

The following references suggest cold storage at around zero degrees Celcius may preserve oil quality for up to a month in storage:

- https://www.oliveoiltimes.com/olive-oil-making-and-milling/freezing-olives-harvest-doesnt-affect-olive-oil-quality/59754

- https://ucanr.edu/sites/Postharvest_Technology_Center_/files/231354.pdf

However we also need to consider how the olives are harvested – if there is damage to the fruit this will accelerate spoilage, also there is a need for rapid removal of field heat – bin size and depth of fruit in bins is critical. There may also be varietal, fruit ripeness differences.

Argentinian olive processing specialist Pablo Canamasas comments:

Some people in Spain kept Picual fruit for 15 days at 4.0-6.0*C*C (fridge temperature) and still got great oil quality, to the point that they won a Gold medal in NYIOOC…

I would not keep olives at 0*C, they would definitely freeze and quality would be touched, regardless of the time spent at that temperature.

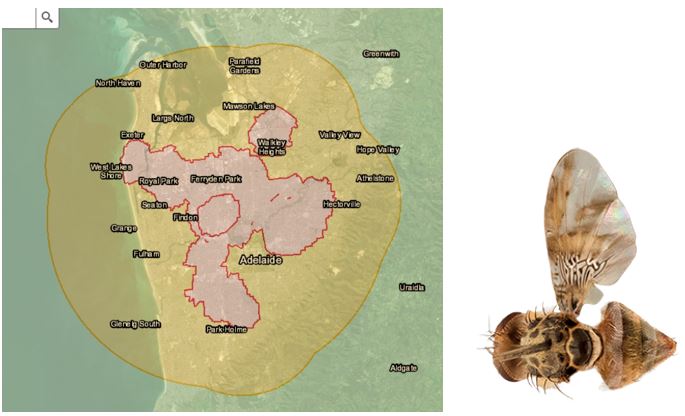

Outbreak of Med-fly in Adelaide South Australia impacts olive growers:

A number of Adelaide olive producers are caught up in the current outbreak of Mediterranean Fruit Fly (Med-fly) Ceratitis capitate, and are unable to send their harvested olives out of the yellow suspension zone into the green zone for processing:

With reference to the PIRSA fruit fly outbreak map below and the Australian tree crop mapping project, map below there appears to be around 4 olive blocks (shown as purple spots) in the Adelaide outbreak area Yellow Zone:

As with the Riverland outbreak the proposed modified ICA-33 fruit movement protocol for olives is currently being negotiated with PIRSA will apply.

Xylella, Olive quick decline syndrome (OQDS), Leaf scorch, Xylella fastidiosa

The Biosecurity Plan for the Olive Industry (Version 2.0 October 2016) identifies the following high priority exotic pests and diseases of olives in Australia – are you able to recognise these?

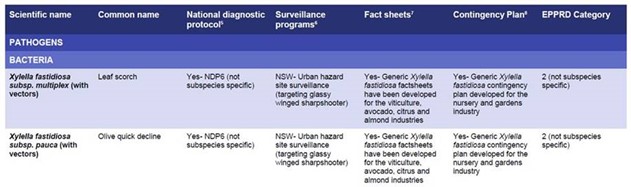

There are two Xylella subspecies that affect olives:

Ref: IPDM Resources (OL17001): Exotic pests and diseases Flier: https://olivebiz.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/EXOTIC-PESTS-AND-DISEASES.pdf

Xylella fastidiosa is a bacterial pathogen that infects over 360 different plant species, including olives. There are several strains (subspecies) of this bacterium; some are limited to certain plant hosts.

At least two strains affect olives and are considered a biosecurity risk as they have not been detected in Australia. They are: X. fastidiosa subsp. pauca and X. fastidiosa subsp. multiplex.

The bacteria live in the plant xylem (water-conducting) vessels, inhibiting the uptake of water and nutrients which leads to disease symptoms that look like water stress – called leaf scorch.

A particular strain of X. fastidiosa subsp. pauca–called Olive Quick Decline Syndrome (OQDS) –causes dieback, and death of trees. OQDS was first reported in olives in southern Italy in 2013, but has since been reported more widely, including in Brazil.

Most introductions of X. fastidiosa occur with the movement of infected plant material. Once present, xylem-feeding insect vectors including leafhoppers and spittlebugs are the primary pathway by which it is spread through a country or region.

Hence, known exotic vectors of Xylella are included in the listed biosecurity threat. There is currently no known cure or treatment for X. fastidiosa infections.

Once plants are infected with Xylella, eradication is extremely difficult; therefore prevention is the most effective approach.

Some olive varieties e.g. Leccino and Favolosa FS-17 appear to be more tolerant while Kalamata, Coratina and Cellina are the worst affected.

Leaf Scorch: Xylella fastidiosa subspecies multiplex (with vectors):

The subspecies X. fastidiosa subsp. multiplex is considered to be a new genetic variant of the bacterium, different to that found in Italy.

Olive Quick Decline Syndrome (OQDS): Xylella fastidiosa subspecies pauca (with vectors)

Symptoms include leaf scorch and desiccation of twigs and branches, beginning at the upper part of the crown and then moving to the rest of the tree, which acquires a burned look. There is no known practical treatment once a plant has been infected and it will eventually die.

The bacterium is transmitted between plants via insect vectors which feed on plant sap (such as the meadow froghopper). Spread of the disease over longer distances occurs when Xylella-infected plants are moved in trade.

Xlyella is currently spreading from the Puglia region of Italy to other Mediterranean olive production regions. The disease has also been detected in olive crops in California, Argentina and Brazil.

Xylella is also known to naturally infect many commercial, ornamental and native plants from more than 300 species, with this number ever increasing.

As it is transmitted by xylem feeding insects, we need to know which insect species in Australia are the potential vectors to effectively target.

Right click on the image and open the hyperlink to watch the video

Xylella resources:

2019 AOA Conference Presentation

Xylella – Act Like It Is Already Here

By Craig Elliott, National Xylella Co-ordinator, Manager National Xylella Preparedness Program

Nowhere has the economic and social impacts of Xylella been more dramatically demonstrated than the olive groves of Italy. With over 560 species of plant hosts and present in multiple regions around the world, Xylella is prioritised as Australia’s number 1 plant biosecurity threat. This presentation covers the key activities of the National Xylella Preparedness Program and key steps growers need to take to protect their properties and businesses from Xylella and other biosecurity threats.

Is Xylella a threat to Australian olives?

December 2019 R&D Insights pp 4-5

https://olivebiz.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/RD-Dec-2019-LR.pdf

Xylella fastidiosa articles in the Olive Oil Times

- International symposium on Xylella fastidiosa (17-18 May 2017)

- National Xylella Action Plan

- Xylella fasidiosa

- Xylella and exotic vectors

- Conference on Xylella fastidiosa October 2019.

- National Xylella Preparedness Workshop

- Workshop outcomes

- Surveillance programs (including Xylella)

- Glassy winged sharpshooter

END